September 2024

Medical Debt, Money, and Mental Health

The Problem

Medical debt affects millions of people, with deep consequences for their lives and families. Medical debt itself is a social determinant of health (SDOH), rather than a symptom—research shows that unaffordable medical bills can lead to a “downward spiral of ill-health and financial precarity,” often trapping people in a complicated cycle of poverty.1 The impact of medical debt redounds throughout people’s lives and across multiple systems; the financial constraints brought on by unaffordable medical bills drive people to defer needed medical care, leading to a cycle of debt, distress, and unresolved health issues. What may have once been something easily addressed with early intervention suddenly becomes a chronic, intractable, and more costly health concern.

Our previous reports with Neighborhood Trust Financial Partners for hospitals and employers highlight that while health insurance offers some protection from medical debt, for many it simply is not enough. In this brief, we explore how incurring medical debt can upend a household, forcing people to choose between basic needs like food and housing and paying their medical bills, ultimately undermining people’s overall health. Finally, we offer recommendations to hospitals on how to mitigate harm for their patients.

Our Findings

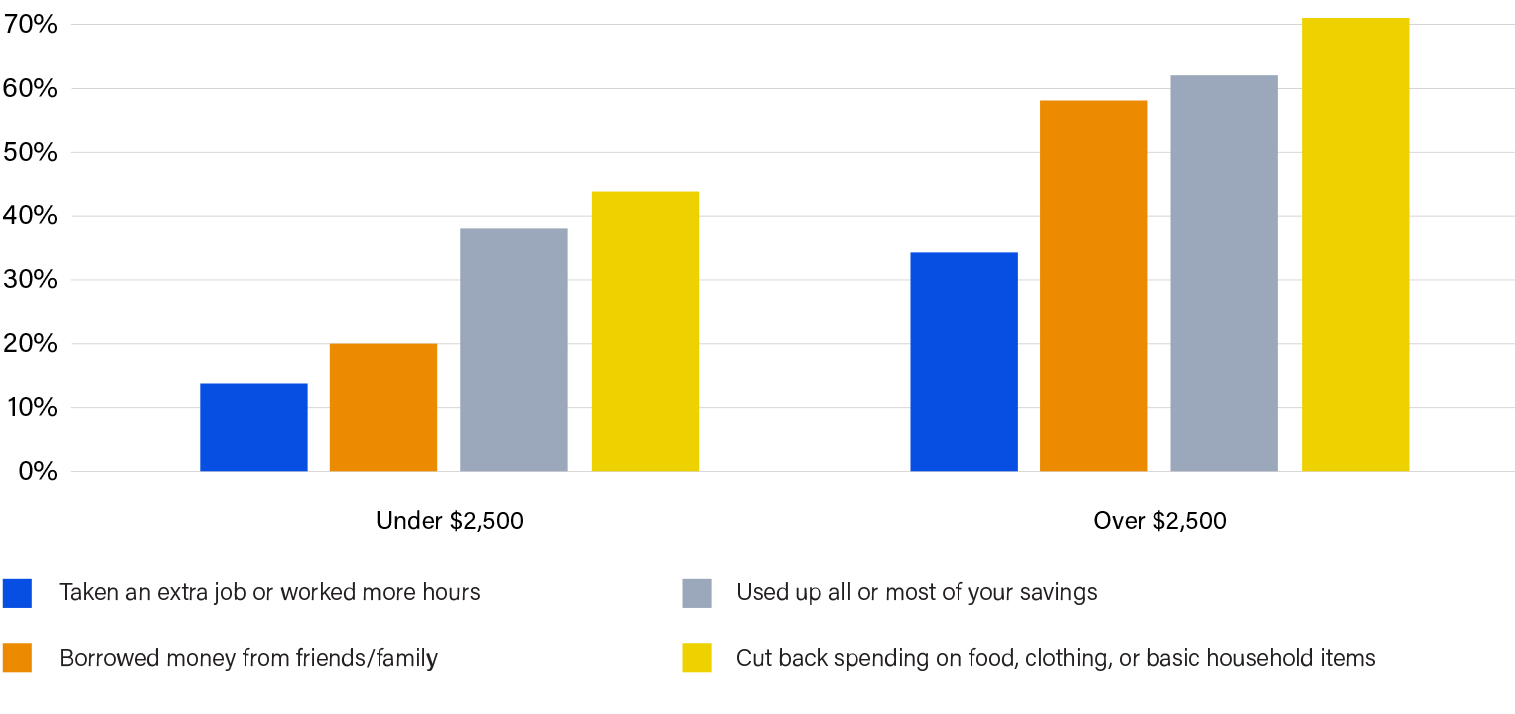

Survey respondents are making difficult financial trade-offs due to medical debt. Three-quarters of our respondents reported household incomes of $60k or less, meaning they are often already having to make hard decisions on where and how to spend their money. With the addition of medical debt, they must weigh making a payment toward their medical debt against buying groceries, often taking an extra job, borrowing from friends or family, and/or using up their savings to try and make the payment (see figure 1).

- 57% of survey respondents with current medical debt reported cutting back spending on food, clothing, or basic household items in the last two years.

- Among those with more than $2,500 in medical debt, this proportion jumped to 70% of respondents (see figure 1).

FIGURE 1

In the past two years, have you done any of the following as a result of medical debt?

It is well-documented that patients struggle to pay unexpected bills over $500, and our survey results only serve to highlight how hard they must work to patch together ways to meet their out-of-pocket requirements. Many people shared how they are forced to draw upon their personal networks, credit cards, or loans to make payments; specifically, patients are quick to leverage credit cards to pay medical bills without appreciating the protections they lose by transforming medical debt into financial debt. Respondents report relying on a combination of their regular income (34%), their savings (17%), some form of credit card (17%), a personal loan/payday loan (6%), friends/family (10%) or a health savings account (10%) to pay medical bills. Others had some of their debt abolished by Undue Medical Debt (12%) or received financial assistance (3%). Of note, 28% of respondents said that they were simply unable to pay. Ultimately, people are expending tremendous amounts of energy in an attempt to pay their medical bills, often at the expense of their health and well-being.

Additional financial consequences included:

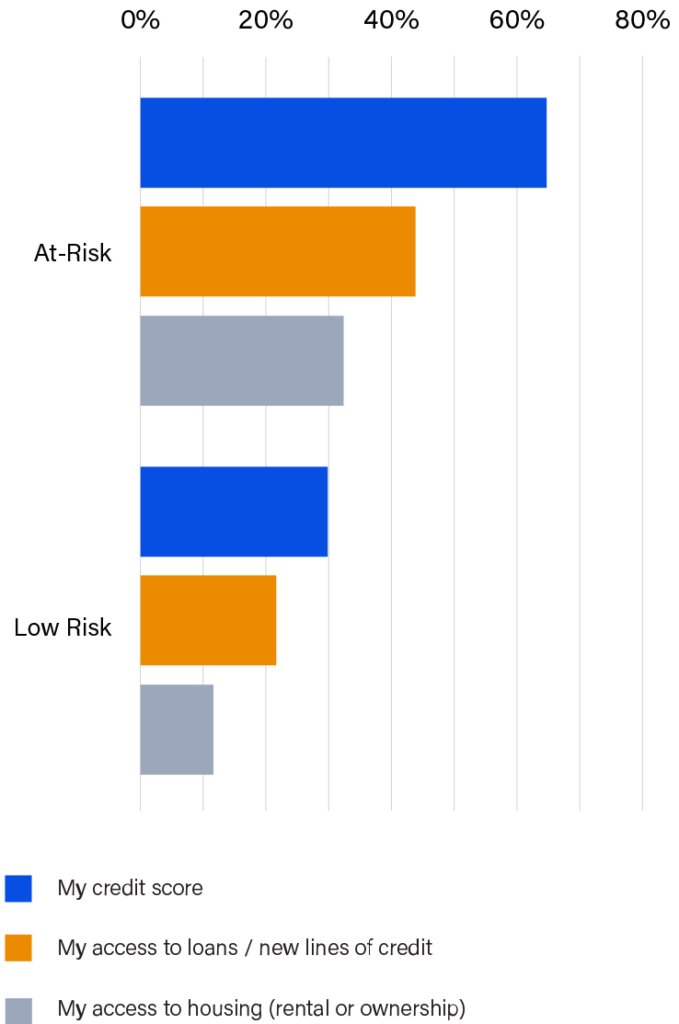

- 68% of survey respondents reported that their medical debt negatively impacted their credit score

- 47% reported that their medical debt negatively affected their access to loans/new lines of credit

- 56% reported that their medical debt negatively affected their plans for the future

These consequences lead to financial precarity, creating limitations on an individual’s and family’s social mobility and decision-making. Access to housing and employment opportunities are limited for many with damaged credit scores. It is tremendously challenging to find the time, energy and resources to think about the future when you’re fighting to stay afloat in the day-to-day.

These effects are outsized for those individuals who we deemed “at-risk” of accruing future medical debt, because they used less sustainable means of paying their last medical bill (borrowed from friends or family, paid with credit card, took out a payday loan, etc.).2 Not only are they at risk of accruing more medical debt in the future, they are also more likely to suffer near term negative impacts on their financial health such as lowered credit scores (64%), reduced access to lines of credit (44%), and greater difficulty obtaining housing (31%). Relying on these unsustainable methods for payment leaves people exposed, potentially destabilizing their lives (see figure 2). Despite recent changes to credit reporting of medical debt, harm to credit scores continues to be a problem.

FIGURE 2

Which of the following has your debt negatively affected?

“I have to juggle gas, utilities, food for my family or focus on my health needs. I have stopped going to the doctor when I know I need to all because I don’t want to get more bills. I also don’t want the embarrassment that comes when they ask how much I am going to pay.”

Cassandra

Survey respondents affirm that medical debt negatively impacts their mental health. The financial toxicity of medical debt adds to the stigma and mental burden of unpaid medical bills. Health concerns on their own can be isolating, and medical debt appears to compound that isolation—survey respondents indicated they find themselves refusing to answer the phone, including calls from their health providers (57%), or open snail mail (39%). Perhaps most concerning, 55% of respondents reported deferring further medical care over the past two years because of their medical debt. Both our survey and the wider body of research indicate people isolate themselves to try and cope with the distress that accompanies medical debt. This is concerning, as research shows feelings of isolation and loneliness are significant risk factors for depression and poor health outcomes; the current system of paying for healthcare runs the risk of making people sick in other ways. Researchers describe the mental anguish that accompanies medical debt as a key part of ‘medical financial hardship,’ which is composed of three domains: medical debt, distress and coping behaviors. Numerous studies highlight the negative impacts of medical financial hardship across cancer and other chronic diseases. 3 4 5

Among survey respondents with medical debt:

- 60% reported negative impacts on their mental health

- 42% reported negative effects on their self-worth

- 21% reported negative impacts on their relationships

Finally, when patients are isolated from the healthcare system, it affects their physical health. Over one-third of survey respondents (39%) said that their medical debt affected their ability to fight their illness. Importantly, people with current medical debt skip seeing their doctor (49%) and reduce or skip their prescriptions (26%) to avoid accruing future medical debt. Concerningly, many people revert to less expensive options like looking up their symptoms online (49%) and attempting to self-treat (48%). We know delaying care can lead to more severe illness and more costly care, and self-treatment can be incredibly risky—and yet many people engage in these risky behaviors that may compromise their financial stability and their health status because they have no other choice. These results show the specter of medical debt may loom even larger than the fear of getting sicker.

These findings are a red flag for health providers that are working to improve patient outcomes, as medical debt erodes the patient-provider partnership and makes the work to overcome illness and poor health more difficult.

“The past-due medical debt we have is due to multiple hospital stays, tests, and surgery for family members. I have tried setting up payment plans which have been denied by the hospital as “not being good enough (amount).” I try to pay what I can without it affecting my family’s wellbeing. It’s extremely stressful to try and juggle bills from month to month.”

Morgan

Why this Matters for Hospitals

Strategies to address social determinants of health (SDOH) increasingly include a role for hospitals; many screen patients for health-related social needs and refer them to community partners, and people struggling with medical bills should be included in this calculus. Without a linkage to these supports, patients may end up sicker and in need of more expensive care, leaving them caught in a cycle of illness and financial precarity. We know medical debt undermines people’s financial security as well as their physical and mental health, and hospitals have an opportunity to counter that disruption. Intervening in this cycle helps maintain healthy, trauma-informed relationships between patient and provider as well as hospitals and the wider community.

While recent voluntary changes in medical debt reporting by national credit reporting agencies are positive steps forward, medical debt remains the primary source of bankruptcy and unpaid medical bills continue to harm credit scores. Hospitals have an excellent opportunity to intervene early in the cycle by helping patients identify accessible pathways to pay for their care or receiving care that is reduced in price—before it becomes medical debt. We know that patients often use credit cards or loans to finance their medical care which transforms that debt into financial debt, which then compounds with interest and is harder to dispute with providers or insurers; many patients do not realize the protections they lose when they finance their healthcare through credit cards and loans. When patients trust their provider and feel safe interacting with them, including medical billing staff, they are more likely to adhere to medical advice and work with providers to settle financing obligations.

“Having medical debt comes with a lot of mental stress for me. It prevents me [from saving] money for myself and my family and for emergency situations. Even with health insurance, I don’t understand the high amount I have to pay out of pocket. It’s very frustrating and stressful to focus on my health.”

Michelle

What Can I Do?

Hospitals are designed to improve people’s health and while they cannot solve the financial challenges many individuals face, they can work to ensure that they are providing patient-friendly financing options, warm hand-offs to social service supports, and ensuring continuity with their patients by tamping down fears about medical bills. The medical billing process is fraught with complexity for both the patient and the provider. Billing departments face high staff turnover rates and are burdened with an increasing volume of insurance denials. There are opportunities, however, to streamline some of these functions that will improve patient quality of care and better align medical billing with SDOH organizational strategies.

Hospitals May Consider

We offer a non-exhaustive list of potential solutions for hospitals below. We recognize that hospitals and providers are stretched thin in providing care to their communities while also balancing their financial needs and other administrative burdens; these solutions are designed to be “win-wins” for everyone, as they help reduce unnecessary administrative burdens while creating a healthier, more collaborative environment for the patient-provider relationship. Simply put, patients who feel they are working in collaboration with—rather than in opposition to—providers are more likely to access the care they need to be healthy and avoid the spiral of ill-health and financial precarity. Providers can, in turn, amend their billing practices/charity care screenings to better account for the financial realities of patients. We offer a non-exhaustive list of potential solutions for hospitals below.

- Reviewing social determinants of health (SDOH) screening tools for financial instability indicators that would trigger financial assistance screening

- Adding a “billing approach” question to patient discharge surveys to get a better picture of the patient experience with billing

- Reviewing all third-party debt collection agency contracts to ensure that these entities are not furnishing to national credit reporting agencies (NCRAs) and requesting these agencies remove any negative credit reporting from past due medical bills

- Screening for financial assistance prior to offering any payment plan and offering only no-interest payment plans or credit cards

- Ending use of deferred interest medical credit cards that may be confusing and harmful for patients

- Revising automated billing systems to notify people when they are found to be presumptively eligible for financial assistance

- Providing training for financial counseling teams on trauma-informed practices recognizing the harmful effects of unpaid medical bills on patients’ mental health as well as the impact on hospital staff. Hospital staff can reframe interactions with patients to be non-punitive and solutions-oriented to ease mental anguish, including leveraging partners like social workers and community health workers to address financing challenges.

“It is too expensive just to go see a doctor or even a dentist. I am a single mother and most of my money goes to bills and food. I cannot miss work because I’ll be short on my pay. So therefore, I try to self-care and Google my symptoms.”

Eileen

Project Background

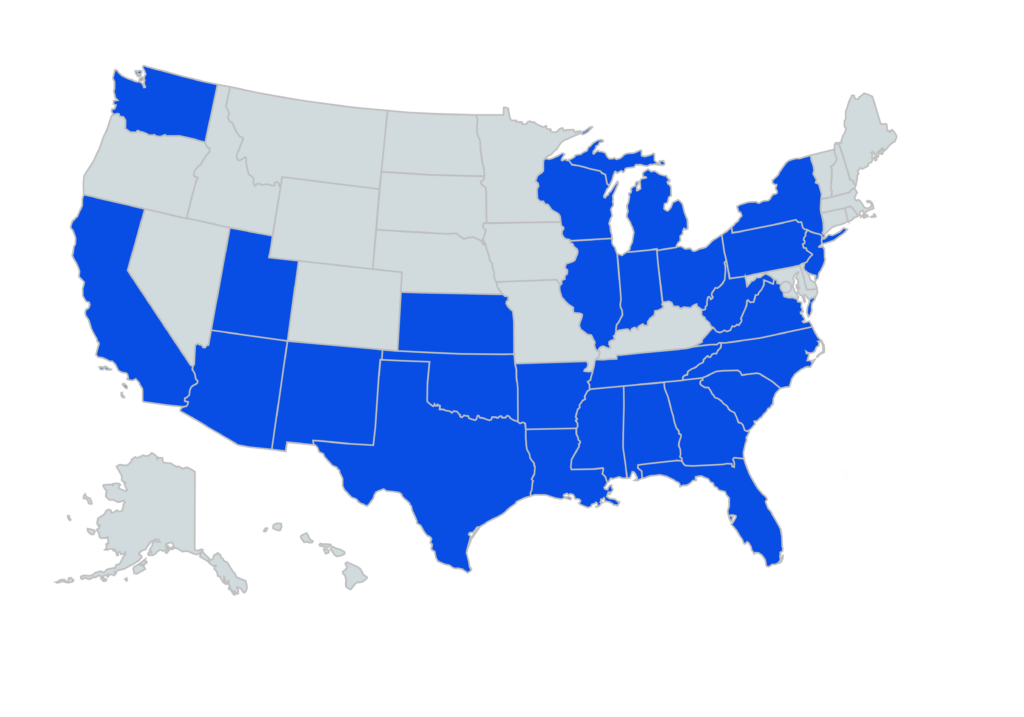

Neighborhood Trust and Undue Medical Debt are partnering to generate awareness, understanding and solutions that enable employers and hospitals to do their part to reduce medical debt burdens, specifically among lower-wage workers. This work will bring the perspectives of low-income workers and those below the poverty line to the forefront of discussions about medical debt and health benefit designs. For Phase 1 of this project, we surveyed 230 low-income individuals, including Neighborhood Trust’s financial coaching clients and those that have benefited from Undue MD’s medical debt relief work. 6 The survey included questions about respondents’ medical debt burdens, the impacts of their debt, and how they accrued it. 7

Survey Respondent Demographics

Participants represented 27 states, with most respondents in TX, MI, SC and FL.

- 76% of respondents reported household income of $60,000 or below.

- 80% identified as female.

- 32% identified as Black or African American, 36% as Caucasian or White, and 17% Hispanic or Latino.

- Average health rating on a scale of 1-5 was a 2.83, with 1 being poor and 5 being excellent.

- 68% reported currently having medical debt.

- 75% of those with medical debt estimated having between $500 and $10,000

- Himmelstein DU, Dickman SL, McCormick D, Bor DH, Gaffney A, Woolhandler S. Prevalence and Risk Factors for Medical Debt and Subsequent Changes in Social Determinants of Health in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(9):e2231898. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.31898 ↩︎

- We deemed respondents at-risk of accruing future medical debt if they relied on any form of credit or informal borrowing rather than insurance or savings, to pay their last medical bill. ↩︎

- Han, X., Zhao, J., Zheng, Z., de Moor, J. S., Virgo, K. S., & Yabroff, K. R. (2020). Medical financial hardship intensity and financial sacrifice associated with cancer in the United States. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 29(2), 308–317. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.epi-19-0460 ↩︎

- Yabroff, K. R., Shih, Y.-C. T., & Bradley, C. J. (2022). Treating the whole patient with cancer: The critical importance of understanding and addressing the trajectory of medical financial hardship. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 114(3), 335–337. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djab211 ↩︎

- Jeon, Y.-H., Essue, B., Jan, S., Wells, R., & Whitworth, J. A. (2009). Economic hardship associated with managing chronic illness: A qualitative inquiry. BMC Health Services Research, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-9-182 ↩︎

- Phase 1 (“Awareness) of this project intends to increase awareness of the prevalence and negative impacts of medical debt, and why it should matter to employers and hospitals to intervene. Phase 2 (“Understanding”) will aim to surface nuanced underlying drivers of medical debt that may be overlooked or misunderstood, and that present innovative leverage points to reduce medical debt, via individual qualitative interviews. And Phase 3 (“Solutions”) will offer recommended solutions for employers and hospitals to take up, incorporating new leverage points revealed in Phase 2 and accounting for implementation barriers ↩︎

- We designed our survey in QuestionPro, with support from the Social Policy Institute at WashU. Several of the questions we included were previously validated by the Kaiser Family Foundation’s research. We emailed the survey to 3,220 Neighborhood Trust clients and 897 Undue Medical Debt beneficiaries, and pledged $5 gift cards for their time. We received 230 complete responses after 3 rounds of outreach. We then conducted X/Y comparison analysis in Excel. ↩︎